With Peter Jackson’s movie version of The Hobbit killing box offices around the world, most people can hardly have failed to notice that, like Spielberg and Lucas before him, Jackson is using his considerable clout to spearhead another leap in technical quality for the cinema experience. I am talking, of course, about The Hobbit‘s release at the projection speed of 48 frames per second, which has already become popularly known by its acronym, HFR (high frame rate).

Jackon’s decision to use HFR for the film was almost certainly prompted by the desire to increase the quality of 3D – something which it indisputably does. Unfortunately, HFR got off to a bad start when news got out that audiences at the CinemaCon preview of The Hobbit in April of 2012, were finding the high resolution experience rather disconcerting. Mostly, the criticisms centred on the HFR looking ‘stagey’ or ‘fake’ or ‘cheap’. Peter Jackson brushed off the criticisms, saying we’d all get used to it, but there is no question that HFR has some ‘issues’. Since the release of the full movie, there have been many dissections of the curious nature of the 48fps effect in the film, some smart and some fairly far-fetched. I have my own hypothesis as to why we have trouble with the HFR experience, but I mostly want to talk about one aspect of that here. And it’s an aspect that no-one seems to have picked up on yet: the sound.

It’s not really that surprising to me, I have to say, that no-one has thought to scrutinize the part that sound plays in the perception problems for a high frame rate experience. People hardly pay attention to sound at the best of times, and in this particular case the whole issue has been entirely one of ‘the look’. A movie, however, is not all about what you see.

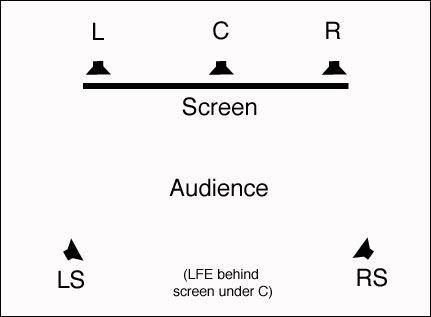

For you to follow my argument in this post, I need to just give a brief overview of the usual experience of sound in the cinema. Currently, most movies you see are delivered to an audience in a format that was first formulated in the 1970s by Dolby Laboratories and then widely adopted in the 1990s for the cinema. It is called 5.1 surround sound (some high end modern movies use a variation of 5.1 called 7.1, but for purposes of this discussion it’s essentially the same thing). 5.1 is arranged in such a way that three speakers across the screen deliver most of the critical sound. These are designated as Left, Center and Right. Usually these speakers are placed just behind the screen, along a horizontal center line halfway down. Two further speaker groups (they are usually groups, but just think of them as single channels, because that’s how they are treated) are designated Left Surround, and Right Surround. These are placed to the side and behind the audience. This array, the L,C,R,Ls,Rs is the ‘5’ of the 5.1, referred to in the profession as ‘5.0’. The ‘.1’ is the Low Frequency Extension, or LFE, which is situated behind the screen with the LCRs, usually on the floor. The important thing about the 5.0 array is that this is what determines the spatial placement of sounds for the audience.

Over the last couple of decades, the surround sound array has proved to be a versatile and durable system, providing considerable enhancement of the 2D experience. Here’s the thing to keep in mind, though: the key to the effectiveness of the whole notion of surround is that the sound can be made to appear to be – fairly convincingly – anywhere inside the theatre in front of the screen. The whole surround sound concept is based on the idea of enveloping the audience.*

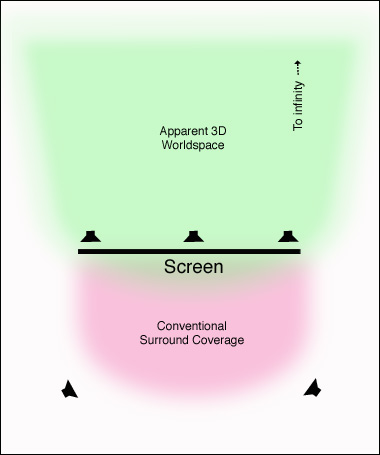

The increasingly fashionable use of 3D over the last five or six years has, however, introduced something new into the movie experience: depth. 3D imaging is, in a way, the complete obverse of surround sound. 3D doesn’t bring the image out into the theatre as much as it expands the depth behind the screen into which the viewer looks. This creates an obvious problem for sound: how do you make the sound feel like it’s back there with the image?

If an object – let’s say a racing car – is on a flat screen (in 2D), then no matter where it is on that screen, it’s always on the same plane as the the speakers reproducing its sound. If the car appears to be receding into the distance, we have learned by cinema sound ‘convention’ that its sound will get quieter (fade away) to make it seem like it’s attached to the car, but in realistic terms it simply can’t appear to be coming from a point source a hundred meters beyond the screen (it’s crucial to understand here that our ears don’t judge the location of a sound solely by its loudness. In addition to loudness, we detect small differences in delay times to place an object aurally in space, as well as as different kinds of reverberation textures and times, and comparisons to other sounds we might be hearing. Our brain’s processing of audio information is complex and detailed, and artificial sound reproduction has pretty much always been a kind of ‘cheat’). As it happens, it’s perfectly acceptable in 2D because the image of the racing car and its sound never actually go off that 2D projection plane.

In 3D in the movies, though, our brains are forced to deal with a kind of cognitive dissonance. The racing car appears to be much more realistically moving at some distance away from us, but we hear the sound that it’s making on the same screen plane as every other sound we’re hearing! In fact, the 3D ‘world’ space and the domain of surround sound hardly overlap at all.

This odd paradox is a legacy of the stumbling technical evolution of the cinema. The whole point of introducing surround sound into the movie environment was to attempt to create another level of involvement for the audience. Because the image on the screen was flat, no-one really thought of having the sound go beyond the screen; like the wall of the cinema to which it was attached, the screen plane has always been treated as a hard and absolute boundary (aside from anything else, there would be the technical and economic consideration of having speakers – and a whole room – on the other side of the screen). The difference between 5.1 and everything since old fashioned mono, was that surround was largely about pulling the sound forward and off the screen, by creating the ambiences of things that you did not see.

With 3D, a whole new space opened up – a space full of things we can see and that can be anywhere from slightly in front of the screen plane to an infinite distance away. And if those things make sounds, then our brains quite understandably expect those sounds to be glued to their matching apparent position in space.

This was never a problem in 2D, because 2D is a stylized way of looking at the world which we have learned to accept as ‘reality’ through massive exposure to 2D images over more than a century, and to which we have become habituated. Up until The Hobbit came along, there wasn’t even much of a problem with 3D, because the quality of 24fps 3D is not really that great and you just didn’t notice the ‘gluing’ error that much. But with the extraordinary detail that is available in HFR, the 3D begins to push a level of resolution that approaches reality. And, as that happens, our brains start to tell us that something is out of whack: “That horse galloping off into the distance! It’s very quiet, but its sound is coming from right in front of us!”

Not that we process it consciously, of course, but it adds to the sum feeling that there is something kind of wrong with what we’re experiencing.

While I was watching The Hobbit this strange dissociation of sound and image kept catching me at every turn: Bilbo runs behind a rock but his footsteps are unattached from him; an arrow hits a distant ledge in a cave and it sounds like a small stick being thwacked next to my ear; a warg runs off into the distance and its growling doesn’t manage to go with it. In general, the whole soundtrack is somehow ‘smeared’ and its details diffuse. Now, I know the guys who did the sound on this film, and I can tell you – they really know their stuff. And I’m willing to bet that when I get to view The Hobbit in 2D here in my studio in 5.1 on BluRay, it will sound spectacular. I believe that the problem is not with the way the sound is done, but with the way the sound is done for an HFR 3D film. The sound for The Hobbit has been created in the manner in which we normally create sound for the surround cinema environment and that process is now approaching a point where it’s simply not adequate to create an illusion of reality.

This difficulty is not confined to the sound alone. In The Hobbit, a similar predicament exists with the lighting and other aspects of its cinematic ‘world’. We’re at a stage with this technology where the whole technical way we make films needs to be rethought.

For sound, I don’t really know how we can easily remedy this situation. One of the other technical innovations that was rolled out for The Hobbit was a new sound format by Dolby Labs called ‘Atmos’ (which unfortunately I didn’t have a chance to experience, since there are no cinemas in the southern hemisphere – other than the Embassy in Jackson’s home town of Wellington, NZ – equipped with it). Dolby understands that as cinema image resolution increases, the 5.1 (or 7.1) array will start to struggle to hold its ground. The Atmos system is an effort to expand the level of detail of, and control over, the aural environment. Atmos employs a speaker array with an astounding 64 programmable point sources throughout the theatre – that’s 58 more speakers than 5.1 – but I’m sure you’re ahead of me here: this hasn’t changed the overall concept of cinema sound. The sound is still inside the auditorium, not back where the 3D is happening. It is likely that Atmos will give a new level of detail to what you hear in the theatre, but it still needs to somehow address the sound on the other side of the artifical boundary that is the screen plane.

Of course, there is a way to tangle with this puzzle, but as I said, it’s not likely to be easy. Or cheap. It involves computers, and sound modelling and other kinds of new tech. It’s rather too complicated to go into at the end of this long post, but maybe I’ll attack it at another time.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

*Director John Boorman, an outspoken critic of surround sound, bemoaned the fact that he’d spent his whole career attempting to get his audience involved in what was happening on that flat screen and now he was expected to embrace a technology that was trying to pull them out of it.

I moderately enjoyed the film in 3D HFR, but am looking forward to relaxing and watching the 2D version at home. This is another inducement. And very interesting. Thanks!!

I’d like to suggest that the huge ‘cinematic treatment’ given to the tale of The Hobbit was simply innapropriate (as you allude to in that ‘other’ place on the web).

Before the ‘EPIC’ LOTR, The Hobbit was this great little adventure story with an unlikely hero… you were amused at his foibles and cheered for him when he triumphed (despite his own self doubt). That is how I read it in ’73. As for Gandalf then, he simply afforded his little friend a chance to be part of an adventure, Bilbo obviously loved to hear Gandalf’s ‘fantastical’ tales of HIS travels and share in some new ‘pipeweed’. His friend Bilbo in The Shire was his little ‘oasis’ of sanity and calm. However, regarding the OTTness of The Hobbit and it’s SFX (having not yet viewed the movie), I feel that the Use of HFR 3D would be more than appropriate in the retelling of the story, from Bilbo’s perspective at least. Listening to Gandalf’s stories (back in the Shire) his imaginings were limited by his (so far) life’s experience. The ‘actual’ experience would have ‘blown his mind’, it was far more than he could had dreamed. Perhaps the movie could also have been treated that way, the lead up events (pre ‘journey’) should have been shot in the lower 24fps to depict the ‘ordinaryness’ of life in The Shire, then again in the end on his return. It could have then been used (to great effect) to highlight his internal struggle in how to put this ‘thing’ to paper (including ‘flahbacks’6 etc)… aaarrrgghh, now I’d better see the movie… so that I might be more ‘on topic’ with my comments.

My point again then, there are times that we simply want to view a ‘flat’ non distracting record of an event (in stereo), times when the ‘telling of a story as a narrative engages us to such a degree that we are ‘drawn in’ to the story… then there are the times that you are ‘there’, part of the ‘reality’, not necessarily standing shoulder to shoulder with the protagonists, but at a safe distance, viewing the scene in HFR clarity, surrounded by the lightning cracks, explosions and screams of plasma cannons… then hearing (feeling) that menacing rumbling presence from behind that builds to a deafening bone rending crescendo above and then around you, exploding into your field of vision as the the prow of a collosal ‘colonial battle cruiser’, on the verge of spewing forth a blast of… AARRRGGH…

….whatever you can get out of that ‘ultra’ 3D XHFR monstrosity you’re using to produce your ‘next generation’ (better than studio quality) blah blah blah… face it, it’ll never be ‘adequate’ (much like my writing 🙂

Oi…. I didn’t insert that ‘smiley’…. damn it, your software took it upon itself to ‘improve’ my comment… d’oh

If you type an emoticon the WordPress engine automatically turns it into the symbolic equivalent. I don’t know if I can switch it off in this ‘free’ version. 😦

Pingback: Sound Problems with HFR & 3D – The Sound of Distant Drumming | ASSG

Pingback: ASSG – Sound Problems with HFR & 3D – The Sound of Distant Drumming